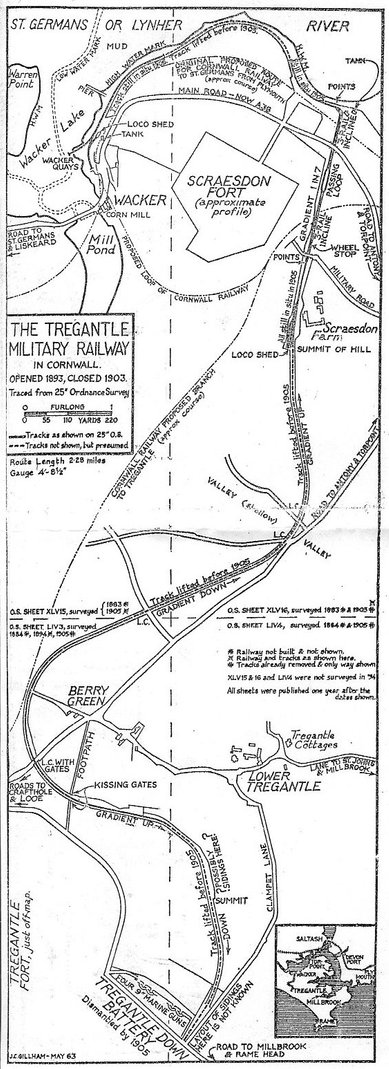

Tregantle Military Railway

Travelling west from Torpoint through Antony and Higher Tregantle on the Crafthole road, one can see, partly concealed beneath many years of overgrowth, two solidly built granite forts,

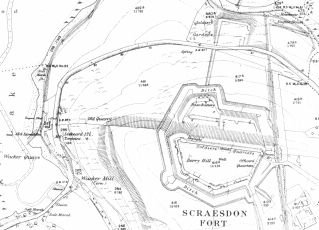

Named Scraesdon and Tregantle, they were part of a series of fortifications that encircled the Port of Plymouth during the mid-19th century to protect the vital naval base at Devonport.

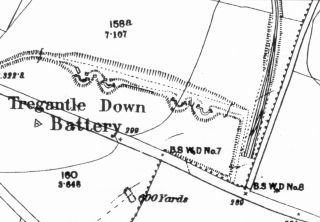

In the early 1890's, Tregantle and the other forts facing seaward were equipped with heavy shore batteries to improve the coastal defences. Tregantle's complement of four 9 inch marine-type guns was set in reinforced emplacements of concrete and red brick and mounted on swivelling platforms at tregantle Down Battery a short distance east of the fort, where they were able to cover an arc of fire across the wide expanse of Whitsand Bay.

A military railwaywas built to serve these installations with a terminus at Wacker, in the upper reaches of the Lynher river to which equipment was conveyed in admiralty barges.

Its rolling stock and probably the track were originally destined to assist in the Sudanese campaign, and in 1885 were shipped to Suakim, on the Red Sea.

Fell Through

However, with the assassination of General Gordon and the fall of Khartoum, the plan fell through and the equipment was all returned to Britain.

After a prolonged period of storage at some unknown military base, the War Department decided to assign the bulk of it to this part of the Westcountry, where in stages, under the supervision of the Royal Engineers the railway was built.

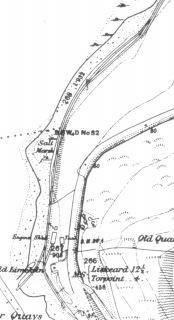

The site's isolation and lack of physical links with any other railway or surfaced highway meant that again the equipment had to be transported by water, and so two sturdily-built pierheads were built by specially-dredged deep channels.

Barges were maneuvered beside the piers by small, powerful steam tugs, but despite intensive dredging, movements were restricted to the top of the tides.

The route, to Higher Tregantle via Scraesdon Fort, involved con¬structing a cable incline, a method that avoided a circuitous detour and reduced expenditure to a minimum. The inclined portion at a severe one-in-seven gradient passed beneath a bridge carrying the Torpoint - Liskeard roadway, which was neatly finished in local granite, its design conforming to standards found on many other railways.

The track had a central common rail and just above the bridge it broke into a passing loop at the half-way point. At the summit and before entering Scraesdon yard. it passed through a cutting as an ordinary single track, and thereafter fanned out into a run-round loop. This yard be came the focal point for unloading all incoming stores, and one siding served a small galvanised-iron engine sheds. The bridge that spanned the cutting that lead to Scraesdon fort's only entrance was a heavy iron structure. From this point silhouetted against the skyline, Tregantle fort can be seen, and before it on a conspicuous ledge, the railway's course.

Kissing Gates

After leaving Scraesdon loop the line descended for approximately half a mile to where it ran alongside the Antony-Crafthole road. There it crossed two narrow lanes and was guarded bay ordinary iron farm gates. After a stiff climb a level spot was reached where it crossed the Crafthole road, and to protect the trains' right of way two heavy-framed wooden gates were installed.

These, netted in thick wire mesh contained safety mechanisms controlled from a ground lever frame designed to locked the gates in whatever position they were left.

Nearing its steepest point a footpath was bisected, and as a precautionary measure two metal swinging gates, of a type commonly known as "kissing gates," were installed. This footpath afforded a useful short cut for soldiers stationed at Tregantle Fort, who would venture into Devonport or perhaps visit the local inn at Antony.

The line in its final stages descended gradually to the massive gun emplacements at Tregantle Down Battery where there was a run round loop and head shunt.

From the bottom of the incline there were two turntables and a head shunt with a track leading back to an engine house, a reservoir was built to provide water for the winding engine. To Wacker Quay the line was a single track with a passing loop close to the quay while at the track ran out onto a jetty with a short siding along the quay with a short spur leading into an engine shed, similar to that at Scraesdon.

The shortage of sidings hindered the engine's movements immensely and made shunting operations quite a problem. It was often found easer to maneuver the trucks by hand on the quay and at the bottom of the incline.

Tree Trunks

The rails were laid to standard gauge and spiked to closely spaced wooden sleepers, which in turn rested on comparative light ballast. The sleepers themselves were cut from 12in. diameter tree trunks sawn into 8ft lengths and sliced longitudinally to produce two apiece.

These were embedded round side downwards and the even surfaces provided accommodation for light weight flat bottomed rails.

Divided by the incline, the two locomotives never met following their delivery. An old photograph of the upper one, shows it to be an 0-6-0 saddle tank built by, Manning Wardle Company in 1885 and bearing their works number 967. Details of its counterpart remain unknown, although records do tell us that 967 was one of twelve. Perhaps the lower engine was another of them. The additional number 334 visible in the photograph was probably given on its return from the unsuccessful mission overseas.

Big Guns

The rolling stock comprised about 15 to 20 four-wheel trucks of the conventional open-sided and flat-bottom types, and certain other information discloses that one enclosed type was kept permanently on the upper level for carrying officers and other ranks between the two forts.

The line was ready for opening about 1893, and its first task was to bring up the massive coastal guns. These were dismantled and transported in sections to Higher Tregantle, where they wore re¬assembled and placed on their respective sites.

From then on in addition to replenishing the magazines after every gunnery practice the railway supplied both forts with every conceivable type of stores, the most essential being rations, coal and drinking water. A number of flat-bottom trucks carrying large capacity tanks were enlisted as permanent water carriers,

View down the incline after closure with the new bridge carrying the Torpont-Liskeard Rd in the centre.

The occasion would appear to be an exercise to build a suspension bridge over the railway cutting

The incline worked on the orthodox counter-balance prin¬ciple powered from a stationary steam winding-house. In exchanging ends trucks were attached to a long spiral wired cable, and when set in motion trucks drawn upwards met the downgrade ones on the passing loop. Its speed is believed never to have been over 15 miles an hour.

Changeover points from two to three rails were automatically switched by the trucks themselves. To prevent accidents when out of use a heavy stop-block slightly below the top points could be set firmly across by moving a hand level.

After each exchange loaded trucks arriving at the top were drawn forward by 967 to Scraesdon Fort's siding, and those for return more often than not empties, were carefully pushed back to the cable connecting point.

On completion of all incline exchanges consignments for Tregantle Fort were segregated and prepared for the last part of the journey. Weight restrictions limited the number of trucks, and ascending the last half-mile 967 would strain its energy to the utmost.

To ensure a clear run a soldier manned the level-crossing gates from where he could see a train departing from Scraesdon and would leisurely open the gates in its favour. In the reverse direction each truck was braked individually until it arrived at the Antony-Crafthole road. After a brief halt here they were released for the gradual climb to Scraesdon.

Ten Years

After surviving barely ten years this project heard its abandon¬ment announced by the War Department when a decision was reached to withdraw the coastal guns. This change of policy was probably due to their costly maintenance and the enormous expense of continually dredging the navigable channels. The railway before finally closing down returned the guns to Wacker Quay, leaving the remaining supplies to be conveyed by road to Torpoint and Devonport. Transport facilities then consisted of horse and mule companies, for mechanical lorries were then only in their infancy.

There is some indication that the line from Wacker Quay to Scraesdon Fort was retained until alternative arrangements were completed.

Some sections of the track were lifted at a very early stage, while the remainder was taken up during a munitions drive in the Great War.

There is some doubt about what happened to the rolling stock and the incline engine house though according to some reliable sources the lower section's locomotive, whose identification was unknown, remained in its shed until the early thirties. In a sorry plight of deterioration it was eventually broken up and taken away by road. The shed was used to by the Cornwall County Council road works department.

Remains

Some of the rails can still be found around Tregantle, for example, as girders reinforcing the butt trenches and guides for running up and down targets.

Above the incline the track can still be traced with difficulty, though below the course is quite impassable because of extensive embankment corrosion and dense undergrowth. The two bridges are still intact, although the granite one has been practically buried in recent road improvement schemes.

The heavy level-crossing gates, which for years rested precariously against bramble and hawthorn hedges, were removed in 1963 when the road was realigned and resurfaced.

Wacker Quay today is a popular pic-nic area, the remains of the jetty can still be seen but the derelict rusty engine shed which for some time was used by Cornwall CC as a highways depot has recently been removed after standin for early 120 year.

No other railway has penetrated this area of SE Cornwall, though originally the Cornwall Railway's proposed route across the River Tamar was between Devonport and Torpoint, there to continue via Antony to St Germans. The Admiralty strongly opposed the plan and demanded that the company retreat farther upstream to where today stands Isambard Kingdom Brunel's famous masterpiece, The Royal Albert Bridge.

From an early undated map that recently came to light, it was noted that in addition to the original proposed main line, which was drawn thickly in red ink, two winding branches that converged on Antony, one from Tregantle via Scraedon and the other from Rame Head via Polhawn, Cawsand, Millbrook and St John.

It is interesting to note that, excluding the last two names, all were either military forts or gun emplacements. Whether these branch lines were to be con¬structed by the military or promoted as a subsidiary to the Cornwall Railway is not known.

Based on an article in the WMN April 1967

Cyber Heritage - Plymouth