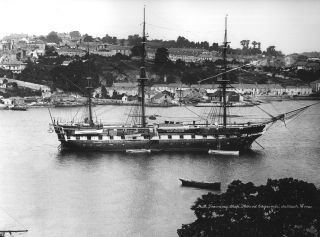

Training Ship Mount Edgcumbe

Training Ship

Homeless and Destitute

Boys

Click on above for a large image |

Few who write about the River Tamar remember the ‘Anchorage for Orphans’ as Marshall Ware called the Training Ship, Mount Edgcumbe. She was anchored in the river, first off Saltash Passage, and then off Saltash from 1877 until Dec 1920.

A training ship often came into existence following a period of public debate in which leading personalities of a locality would become involved. Behind such activity there was usually the interest and energy of one or two individual philanthropists. It is not clear who the moving spirit was behind the establishment of the Mount Edgcumbe but the inaugural meeting was held in Plymouth on 5th November 1874, with parallel meetings in Stonehouse and Devonport. The Mayor of Plymouth chaired the meeting, Mr. Woodward described the work of the Formidable (a training ship in Bristol) and Mr. W.F. Moore moving the establishment of a ship revealed that the Admiralty would provide a vessel. A committee of thirty three persons was elected. Thus the Devon and Cornwall Industrial Training Ship Association was formed. In practice a ship could not be managed effectively by such a large group. The day to day management inevitably developed around a small group of persons prepared to give their time on a regular basis.

The ship was, originally, H.M.S. Winchester and then renamed the Conway in 1861, and the MountEdgcumbe in 1877, when she was used to serve as an Industrial Training Ship for Homeless and Destitute Boys. The training provided by the Mount Edgcumbe, like other training ships was in seamanship, tailoring, shoe making. These lads did their sea-training in the Goshawk, after which ship the Goss’s named one of their eighteen-foot watermen's boats.

When Mount Edgcumbe opened in June 1877, donations had reached £3,408, and £525 had been promised in annual subscriptions.

The Industrial Schools Act, 1866 allowed any person to bring any child under the age of 14 years before a magistrate. If the child was found to be in need of care and protection, he could be committed to a certified industrial school. for as long as was considered necessary, but not beyond the age of sixteen years. The child might be sent to any school on shore (or a training ship) which had space and agreed to take him. The training ships were probably favored for the more unruly cases as they were run on naval lines and the discipline was considered to be stricter than that at other schools. The register books give the reasons for committal, which include; ‘theft’, ‘company of known thieves’, ‘begging and associating with thieves’, ‘truant’, ‘beyond control’, ‘non-attendance at school’. A frequent entry was simply ‘found wandering’. In such cases it might be expected that an adverse entry on the character of the parents would be recorded, yet terms such as ‘sober’ or ‘steady’ frequently appear. Although children under the age of 12 years charged with an impressionable offence could also be sent to an industrial school, children in such schools had not been convicted.

The intake to Mount Edgcumbe was not restricted to boys belonging to the surrounding district, many boys coming from other parts of the country particularly the London area. (in 1896 out of 68 boys admitted, 51 came from London).

It is interesting to learn that although those who lived at Saltash Passage accepted the boys, Saltash residents feared, suspected, and shunned them until the owner of the Saltash Gazette, Mr. Dingle, reassured them that the boys were well-behaved. They had to be; they were strictly disciplined.

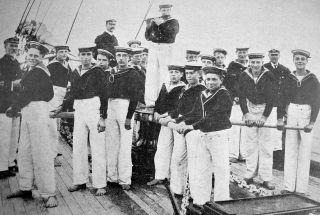

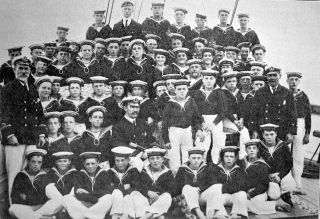

A boy sent to the Mount Edgcumbe would have found himself drawn into a way of life which was certainly a marked contrast to his previous existence. While his personal needs of food, clothing and housing were provided, the very full daily routine occupied all his working hours from 5 : 50 in the morning to 8 : 00 at night throughout the year. Of this time about one and a half hours would have been spent at meals, three hours each at ‘housekeeping’ duties, ‘school’ and seamanship, etc., and the remainder at recreation and other miscellaneous duties. The boys were divided into two watches, port and starboard, during the morning, while one watch was at ‘school’ the other was at seamanship; during the afternoon the roles were reversed. The accommodation was divided into a number of divisions with each division sub divided into messes. Each division contained about 30 boys and was supervised by one member of the staff aided by two or three senior boys. The messes were smaller units which functioned at meal times; each boy in turn would serve food in his mess. There were numerous other duties which boys took turns at performing, such as post boy or messenger. In fact the organization of the ships simulated that of the adult world of the Royal Navy.

The watch on deck was divided into various groups supervised by seaman instructors. All the skills of the practical seaman were taught including knots, splices, canvass work, sail handling signaling, sounding and compass work. For safety reasons the ‘Abandon Ship’ drill was thoroughly practiced. Each boy also spent time working under the supervision of the cook, the tailor, the carpenter and the shoemaker. The watch below was meanwhile at school on the main deck, immediately below the upper deck. Except for a section towards the bow and stern of the Mount Edgcumbe which had been partitioned off for the staff accommodation, the galley, stores and boys’ bathroom, the main deck was a large open space which served, as occasion required, as dining room, assembly hall, class room and recreation room. For school the boys were divided into classes according to their standard of reading, writing and arithmetic, all classes being together in the same space.

At the end of the school period the desks were stowed away and replaced by tables and benches for the meal which followed. Although the main deck was one large open space, invisible boundaries ‘marked’ the area occupied by a particular activity, and a boy wishing to enter or cross an area was required to ask permission. At meal times, for example, each mess occupied such a space.

Mount Edgcumbe was equipped with a small library, an organ, brass band instruments and a variety of games. During the evening the main deck became the scene of several recreational activities. At the end of the day hammocks were slung in the lower deck, below the main deck which served as a dormitory.

Because training ships were residential establishments there had to be a staff presence 24 hours a day. This was normally maintained on a rota basis by the Captain-Superintendent, Chief Officer and Seaman Instructors, all of whom normally had naval backgrounds. The Captain-Superintendent was required to live on board, with his family, in spacious accommodation at the after end of the ship. The other staff lived ashore but had their own cabins on board as they kept duty on alternate nights and alternate weekends. At night, on the MountEdgcumbe, watches of two hours duration were kept by one member of staff aided by two boys.

When the Mayor of Plymouth (Mr. W. Derry), accompanied by Mr. S.S. Lloyd, M.P. and 'ladies and gentlemen', visited the Mount Edgcumbe to be received on board by Capt. Knevitt, R.N. and Mr. G. Chase, the secretary to the committee which promoted the institution and raised money in both counties to fit out and equip the ship, he found every boy being instructed in useful work. He saw boys being taught to read, spell, do arithmetic, understand English grammar, to read the compass, and make canvas suits. On the lower deck, keen young sailor-lads were being drilled, "each being supplied with a miniature carbine, and the manner in which they went through the evolutions was exceedingly interesting. The ship is a pattern of neatness and order, and the boys looked comfortable and happy."

Opportunity for the boys to leave the ship were not very frequent. Saturday afternoons were set aside for games in a field to which the ship had been given access, but especially in winter, this could be prevented by bad weather and there were times when the waters in Saltash Passage were too rough for any of the ship’s boats to be operated. Home leave seems to have been rarely granted, although a few boys were allowed home at Christmas. There was however greater opportunity for shore leave during the summer months, especially for the ships band which was invited to play at local fêtes. Relief from the confines of the ship was also given by the ample experience in small boats which was provided by the MountEdgcumbe’s fleet of craft that in 1898 included a 7 ton yawl, 4 cutters and 3 gig’s. In 1899 these were joined by the 107ft Goshawk.

In 1910 Capt. H. Wesley Harkcom was appointed Captain Superintendent. The captain was a rowing expert and "a very fair and just man" he had been Master of the Goshawk since 1903 and well known in the area. He set about reforming the ship, two of his first actions were to drop “Industrial” from the ship’s name and to ban the use of the birch.

unit as any contagious illness on board the Mount Edgcumbe could soon spread in the cramped conditions. The death, accident and illness rates on schools afloat were much higher than that of a similar establishment ashore.

In 1860, the ship's cottage hospital had been built on the embankment (built on reclaimed mud-flats of the river) by a Mr. Elliott, who, appropriately, called the hospital "Newlands Cottage Hospital"

The Devon and Cornwall Committee's dignitaries included the Prince of Wales (Patron), the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe, Earl Fortescue, the Earl of Morley, Viscount Valletort, Sir Henry Lopes, Bart., Lord St. Levan, the Hon. Waldorf Astor, M.P., General Sir R. Pole-Carew, Sir C. Kinlock Cooke, M.P., and Sir John Jackson, M.P.

The hospital was well used, not only to treat illnesses and boys who had accidents but as an isolation

The Mount Edgcumbe was licensed for 250 boys. During the Great War Capt. Harkcom claimed proudly that not very many ships in the Royal Navy were without one or more of his old boys on board. Some, however, joined the Army and the many the Merchant Service.

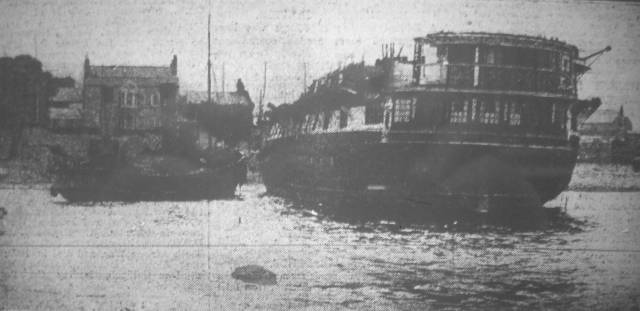

The ship closed down in December, 1920, all the boys being ‘suitably placed’. The ship was then towed to Queen Anne's Battery, where she was broken up. Capt. Harkcom was allowed to live in the hospital until 1926, when it and the land was acquired by the War Department. Two of her guns were brought by Mr. Ware's father in 1922. He lent them each year to the St. Budeaux Regatta Committee until 1928, when they were stored in a cellar. However, they were lent on a permanent loan to the Commodore of the Royal Albert Sailing Club when it was formed in 1932.

Mount Edgcumbe being scrapped at Queen Anne Battery

T.S. Mount Edgcumbe

Training Ship for Homeless and Destitute Boys

(96 pages A4 fully illustrated)

Available £12.95 inc post to a UK address

Contact Bruce at Bruceehunt@Yahoo.com for details