A Tunnel under Saltash

The Tunnel

In 1976 the long awaited proposals for the new trunk road from the Tamar Bridge to Trerulefoot, linking up with the new by-pass for Plymouth, running in a direct line through the city from Marsh Mills to the Tamar, were published by the Dept. of the Environment.

Views of the public were sought at once with exhibitions of the plans being arranged for Landrake and Saltash.

Two alternative routes were put forward, one passing to the north of Tideford and Landrake and the other to the south of these villages. Only small portions of the existing trunk road would be incorporated into one of them.

Greatest interest in the route was centered on how the proposals affected Saltash as the town has been under threat of several suggestions for some years.

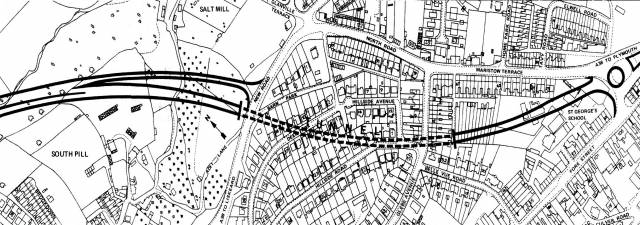

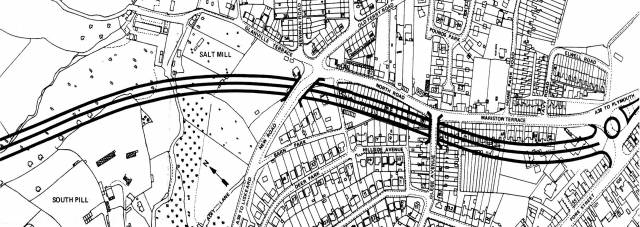

As can be seen from the accompanying maps there were two alternative routes through the town. Both involve a reconstructed roundabout at the Saltash end of the bridge taking away Brunel Green and the burnt out North Road school.

In a tunnel

Scheme A from that point would be only a two-way road and after cutting across the gardens of Maristow Terrace, in a gradually deepening cutting, the road would disappear into a tunnel before it reaches Glebe Avenue.

The tunnel would continue under Glebe Avenue. Hillside Road and Deer Park and the road would emerge into a cutting just north of the present A38 and then continue on an embankment 24ft. high south-west of Salt Mill and become a dual carriageway.

This scheme was the more acceptable one for Saltash as no demolition of occupied properties were involved. The tunnel would also eliminate the nuisance of noise.

43 houses lost

Scheme B would be a dual carriageway all the way from the new roundabout at the Saltash end of the bridge. It would involve the demolition of the houses at Maristow Terrace and the south side of North Road going under Glebe Avenue.

It would also pass under the existing A38 just west of Glanville Terrace. The road would he in a cutting up to 42ft. deep and then would he carried across the valley to the south west of Salt Mill on an embankment up to 30ft. high.

This route would involve the demolition of 43 houses but the cutting and retaining walls, it was claimed, would have the effect of reducing the visual and noise effect on adjacent properties.

The cost of Scheme A (the tunnel one) was estimated to be £4.060.000 and Scheme B was £3.500.000. It was thought that scheme A. with only a two-way tunnel and section to the Saltash end of the bridge might, at some future date depending upon the volume of traffic need another tunnel to be driven alongside it to make it into a dual carriageway.

It can be seen from the map that if Scheme A was chosen traffic from the Liskeard direction, not wishing to go over the TamarBridge could take a slip road which links up with the present A38 at New Road and would give access to central Saltash.

This slip road would be used if an accident prevented the tunnel from being used or while maintenance work was in progress.

North of Burraton

After leaving South Pill at Saltash, two alternative routes were put forward for public consultation. The southernmost route would be in a cutting as it goes north of the Burraton traffic lights, under the Saltash to Callington road, through the Moorlands trading estate to Latehhrook and then take the route of the present A38 to Stoketon Cross.

The more northerly route would pass between Higher Pill and Pill Farm under the Saltash to Callington Road where there would be a junction to the A388, and then on to Stoketon Cross.

The D of E favoured the cheaper option of a dual carriageway but a vociferous campaign by Saltash residents who thought that a dual carriageway would in effect cut the town in two favouredthe tunnel plan and eventually won the day.

The tunnel won the day but plans were modified by increasing the planned carriageway to three lanes, replacing the roundabout at the end of the bridge with an underpass and replacing the planed underpass with the Callington road at Carkeel with a roundabout.

The tunnel was designed by Mott, Hay and Anderson, built by Balfour Beatty, and has a design life of at least 100 years. Before the tunnel was officially opened by the then Secretary of State for Transport, Paul Channon, cracks began to appear in the lining only months after completion.

Although the cracks were not problematic to begin with, water soon began to seep through them—not clean water, of course, but extremely dirty water, so the appearance of the tunnel gradually deteriorated, the structural integrity of the tunnel, which is almost a quarter of a mile long, was not in question.

During construction of the tunnel a problem was encountered with flooding due to the saturation of the surrounding rocks. The resultant flow of water was channelled through the tunnel, hidden by a decorative cladding. Within a few months this cladding had begun to crack and water entered the part of the tunnel reserved for traffic; although no structural problems were found the water staining on the cladding gave the impression of a poorly built tunnel. This was commented upon in Parliament by the local MP, Colin Breed, and a £7.4 million renovation project was contracted to Skanska to provide for a new tunnel lining and improvements to the electrical system.