Royal Albert Bridge - Renewing the land spans

The Royal Albert Bridge has stood in tribute to the engineering skill of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and as a Saltash landmark since 1859, it has remained virtually unaltered for 150 years although the weight of locomotives and trains crossing the bridge has increased considerably. In 1860 the weight of a Cornwall Railway saddle tank was about 40 tons with an axle weight of 14 tons. This increased to 16 tons with the conversion to standard gauge in 1892, the main motive power then being 4-4-0 Duke and Bulldog class loco’s.

In 1905, the bridge was strengthened and stiffened with the addition of 401 new cross girders and in 1908 the first two land spans at the Cornish end of the bridge were reconstruction to enable the double line at Saltash station to be extended onto the bridge.

By WW1 4-6-0 Star and Saint class locomotives were in service with an axle weight of almost 19 tons. By the 1920’s the bridge had been in service for over 60 years and although the bridge structure itself was in good condition the land span main girders were suffering corrosion at their base, so in 1928 it was decided to replace the main girders of the remaining fifteen land spans.

This provided an interesting engineering problem, for the physical conditions ruled out all methods usually adopted in bridge reconstruction work. Cranes could not stand and slew on the bridge, and further, owing to traffic requirements, occupation of the single line could only be given for limited periods.

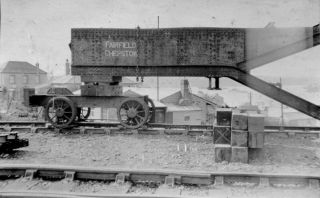

The probability of the land spans requiring renewal sooner or later had, of course, been in the minds of G.W.R. engineers for some time past, and a method of reconstruction had been approved in principle by the Chief Engineer. The scheme eventually adopted was the use of a specially designed vehicle, which came to be known as the ‘erection-wagon’ of such a size and shape that it would:-

(a) Carry two new main girders, one on each side of it, from the temporary constructional yard nearby, to the particular span for which they were made.

(b) Deposit them on their piers, in position between itself and the old girders which they were to replace.

(c) Carry the whole of the floor while, with specially designed gear, it picked up the old girders and deposited them in temporary positions outside the permanent positions of the new girders.

(d) Place new main girders in permanent position.

(e) Pick up the old main girders and carry them to the temporary yard for cutting up.

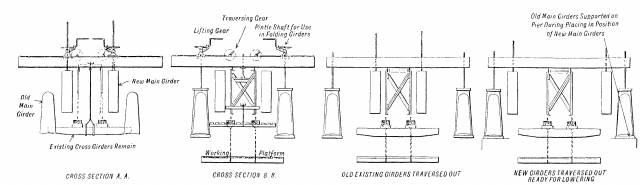

This vehicle was of lattice design, 95 feet long (in order to bridge the longest span) and weighed about 18½ tons. Attached to the top boom were transverse girders forming four cross members, and within each pair of cross girders were fixed lifting and traversing gear, all tested for a working load of 15 tons.

Fixed on the underside at each end were box girders, 12ft. in length (adjustable as their positions would vary on each span) which rested on stools and carried the total weight during the time when the replacement of each of the girders of each span was being effected

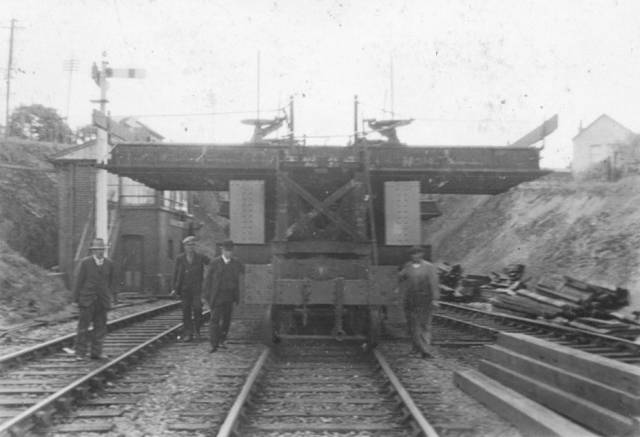

The erection wagon was provided with two standard engine bogies, with special wooden bolsters. The total weight of the wagon when carrying the old and new girders, etc., was approximately 80 tons.

There was, of course, a certain amount of preliminary work before bringing the ‘erection-wagon’ on the scene at all. This consisted chiefly of the providing of close decked suspended scaffolding under each of the spans, laying a longitudinally supported track in the place of the former cross-sleeper road, separating (by means of oxyacetylene plant) the original cross-girders, and so forth.

The actual job of replacing the land spans was carried out on Sundays when the traffic was comparatively light. The times of certain through trains were temporarily re-arranged, and the local services to Saltash were run between Plymouth and St. Budeaux station where passengerstransferred to road motors to be conveyed to the ferry across the Tamar. Absolute occupation of the main line was obtained for limited times, during which the original cross girders were removed, the old timber decking renewed, and the new main girders unloaded from the crocodile wagons on which they arrived from the makers, and placed in position alongside the erection-wagon in the siding. On the Sundays when the main girders of each span were renewed, the occupation of the line extended from about 9 a.m. to 2 p.m.

The general procedure for renewing a span started with the ‘erection-wagon’, complete with the new main girders suspended from it being drawn slowly out of the siding by a locomotive on to the main line and then propelled on to the bridge and positioned over the span to be renewed. The steel stools of the ‘erection-wagon’ were then fixed in position over the piers and the erection-wagon girder itself was lowered on to them.

The bogies of the erection-wagon having been run clear of the work, the permanent way and cross girders were then attached to it and the new main girders were lowered on to temporary packing on each pier, thereby removing their weight from the erection girder. The erection-wagon was then lifted bodily by four 40-ton hydraulic jacks and set on cross timber beams inserted on the top of the stools, this lift raising the cross girders sufficiently to clear their supports on the new girders and to draw the shackles tight on the bottom flanges of the old main girders.

Everything now being clear, the four men detailed to each of the four main screws (with one additional man to check the horizontal and vertical movements to ensure all were working together) lifted the old girders and moved them outwards to positions where they would clear everything when drawn off the bridge. The new main girders were then travelled outwards and lowered to permanent position; the bridge floor, which had been suspended from the wagon, dropped on to them, and the permanent way restored.

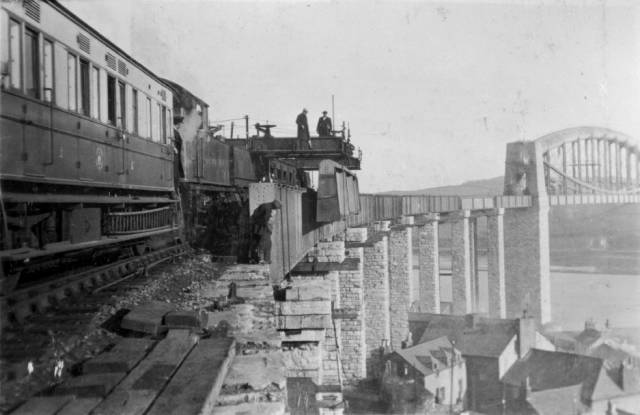

At this stage of the operations, the old main girders are suspended from the overhead traverse girders and as can be seen in the photographs the ‘erection wagon’ end is being transferred to its bogie preparatory for the journey back to the construction yard.

During the periods between the Sunday occupations, the work of cleaning, painting and riveting proceeded. The whole of the reconstruction was carried out by the Great Western Railway Company's staff, the average number of men employed on each Sunday being about 46. The average time taken in reconstructing a span was about three and a half hours.

This procedure was repeated for all spans except the two innermost land span girders, which were housed in the casing of the main piers, and to enable these to be withdrawn and replaced by new girders, a travelling platform was designed and fixed at each end of the erection wagon; after the old girders had been lifted as previously mentioned, they were transferred to the traverser, drawn out of the portal and connected to the main screws, and the new girders run into the final position by similar means.

The replacement of the land spans on the Saltash end of the bridge was a repeat of the St. Budeaux side except that the ‘erection wagon’ would only fit through Saltash Station unloaded because of the curve, so the new girders were loaded onto the ‘erection wagon’ at the bridge end of the station.

The replacement of the land spans, particularly on the Saltash side of the river was at the time quite a big local event and well documented. The GWR took a number of publicity photographs at the time, mainly of the work as it progressed but some pictured the Waterside from a not often seen angle.

In 1930 lateral bracing was fitted and in 1966 a test programme was initiated to investigate the stress that would be induced in the two main spans by a train of four axle vehicles each with a gross weight of 100 tons, equal to 25 tons per axle. This resulted in 48 new diagonal members of steel to restrain the shearing action between the track girders and the chains.